By

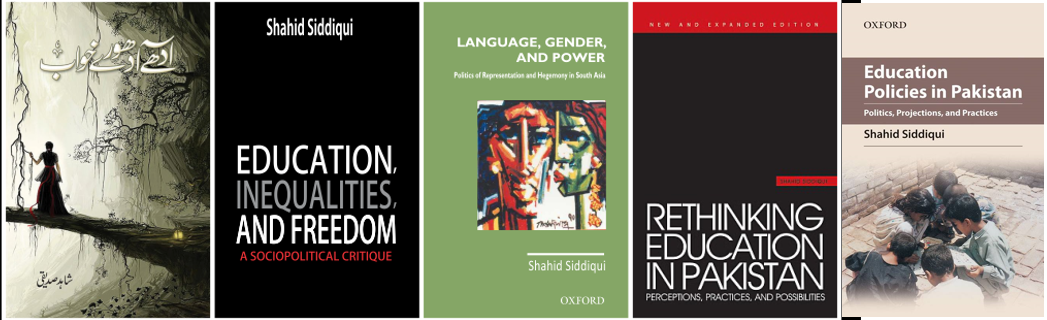

Dr Shahid Siddiqui

Dawn, Monday, 27 Sep, 2010

LANGUAGE and society have a two-way relationship. On the one hand, social factors such as age, gender, social relationships, class, and religion influence language. On the other hand language, in a relatively subtle way, impacts the world in general.

This phenomenon was underlined by the Sapir-Whorf hypothesis that suggests that language is not merely a passive tool but is actively involved in the creation of the perception of the outer world, and the construction of social reality. Language thus emerges as a powerful manifestation of culture that acts as an identity marker at individual and societal levels. There is a strong link between the language users’ beliefs, their language and their understanding of the world since the world is perceived, understood, interpreted and represented along lines of thought that are unique to each language.

Keeping in view the centrality of language in individual and societal lives, it is shocking to learn that a number of languages are facing the threat of extinction or contraction. If we look at the human history we do find incidents where languages have disappeared, yet the alarming fact about the present situation is that the rate of extinction has accelerated by many times in the contemporary world.

Currently, according to Ethnologue (2009), an encyclopaedic reference work that catalogues the world’s living languages, just under 7,000 languages are spoken in the world but the distribution of their speakers is far from even. For instance, according to linguist David Crystal, just 4 per cent of the world’s languages are spoken by 96 per cent of the population. In other words, 96 per cent of the world’s languages are spoken by only 4 per cent of the population. A Unesco report estimates that about 2,471 languages are endangered.

Historically, we see two approaches to the issue of language. The first can be called the ‘melting pot approach’ that believes that there is no justification for the existence of a number of minor languages — that they should be put into the melting pot of the dominant language that represents power. This approach was advocated and practiced by imperial powers as they tried to impose their own language over native populations and ignored the local languages. Deep down in this approach one can sense, as Edward Said might suggest, a sense of positional superiority. The different dominant groups in a given society try to promote and impose their own languages on the marginalised groups. It is important to note that language is the main constituent of discourse that plays a vital role in the dynamics of power. A number of scholars, from Gramsci and Derrida to Foucault and Fairclough, have focused on the role of the discursive approach in obtaining and sustaining control over others.

The competing school of thought opposes the melting pot approach and maintains that there is beauty in diversity, and thus every language has the right to exist. According to the adherents of this school, linguistic diversity is as important as biological diversity.

But this diversity is at risk now, as languages are dying fast. This can be attributed to a number of reasons, including natural, cultural, social, economic and geographical factors. One major factor that has dwarfed others is the pragmatism that forms the basis of modern globalisation. Social, cultural and geographical reasons are in a subtle way linked to the process of globalisation. For instance in Pakistan, English — being a symbol of power — is associated with the elite. In order to align themselves with the elites, people would use English. At another level Urdu is at a similar vantage point as compared to the local languages of the country such as Punjabi, Sindhi, Pushto, Seraiki etc. It is important to understand that no language is superior or inferior in itself. It is the socio-economic status of the speakers of a certain language that bestows it strength.

In Pakistan, about 66 languages are spoken in different parts of the country. The main languages, Punjabi, Pushto, Sindhi, Seraiki, Urdu and Balochi, are spoken by 95.34 per cent of the people whereas the remaining sixty are spoken by 4.66 per cent of the people. According to a 2009 Unesco report on endangered languages, 27 Pakistani languages are facing the threat of extinction. These include Balti, Bashkarik, Bateri, Bhadravahi, Brahui, Burushaski, Chilisso, Dameli, Domaaki, Gawar-Bati, Gowro, Jad, Kalasha, Kati, Khowar, Kundal Shahi, Maiya, Ormuri, Phalura, Purik, Savi, Spiti, Torwali, Ushojo, Wakhi, Yidgha and Zangskari.

Most of these languages are spoken in the mountains. With the advent of globalisation the compact community system and their cultures and languages are at risk. The young people of such linguistic communities are moving to large cities in connection with their education or jobs, where they have to use Urdu or English in order to assimilate. Another important factor is the attitude of policymakers towards certain languages. This complacent attitude is common among authorities at the local and federal levels. No serious measures have been taken to legitimise such languages.

The extinction of a language would not just mean the disappearance of a number of words and expressions. In fact, it would translate to the loss of identities, the death of particular viewpoints and the extinction of social histories. We need to act now, and fast. Some serious measures need to be taken to save Pakistan’s dying languages. Such actions can be taken at the local level by interested groups and organisations, which ought to be supported by the state. As Ezra Pound said, “The sum of human wisdom is not contained in any one language, and no single language is capable of expressing all forms and degrees of human comprehension.”

The writer is a professor and director of the Centre for Humanities and Social Sciences at the Lahore School of Economics and author of Rethinking Education in Pakistan.

http://shahidksiddiqui.blogspot.com

Email: shahidksiddiqui@yahoo.com