by

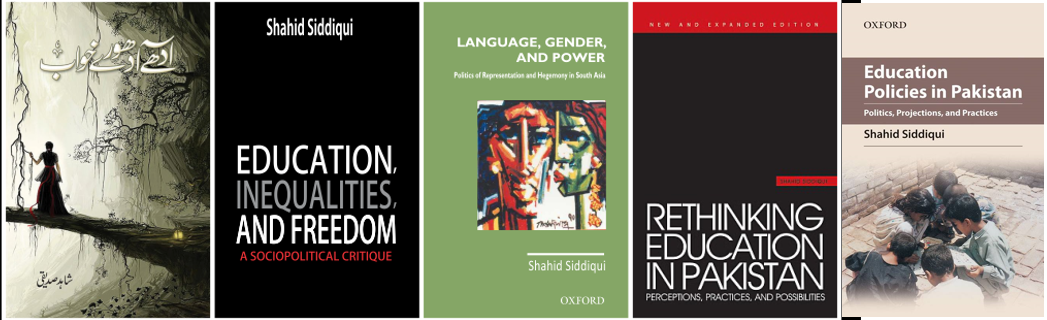

Dr Shahid Siddiqui

http://www.pakistantoday.com.pk/2011/09/crisis-of-implementation/

18 September, 2011

History of education in Pakistan is filled with ambitious promises, half baked educational plans, and poor implementation mechanisms. Besides other important factors a major reason of failure in education is the absence of political will. This is closely linked with the lack of prioritisation of education in terms of funding, monitoring and accountability.

A quick glance at the educational reforms in Pakistan tells us that most of the reforms were initiated on the whims of individual rulers, supported by donor agencies, without much thinking and planning. There has always been a centrist mindset of the elite ruling class that concentrated all rights in the centre and dissenting voices from the periphery were suppressed. Usually, this suppression was done in the name of patriotism. The peripheral forces that raised voices for their economic, political, linguistic, and cultural rights were dubbed as traitors and anti-state agents.

One prominent example is the reaction of the centrist powers towards the rightful demand of people of East Pakistan (now Bangladesh) to declared Bangla as one of the national languages of Pakistan. The opposition to this demand led to a lot of bloodshed and played an important role in widening the rifts between the two wings of the country.

Pakistan has been ruled by the military dictatorship for most of the time that called for a centrist mindset and prompted the idea of a unitary state. The 1973 constitution that was prepared by consensus of major political parties had certain welcome provisions for provincial autonomy. Unfortunately, these provisions were not implemented according to the spirit of the constitution. For instance, Council of Common Interest which could be a very important means of maintaining inter-provincial harmony was not utilised effectively. This is evident from the fact that since 1973 only eleven meetings of this council have been called.

With this background of non-participatory and centre based approach, 18th amendment was seen as a welcome step. It had its roots in the Charter of Democracy. On 10th April 2009 the National assembly and on 29th April 2009 the Senate passed resolution to form a committee to reform the constitution.

To develop a broad-based consensus, the committee invited citizens’ suggestions and political parties’ position by 10th August, 2009. To thrash out details and incorporate different points of view, the committee worked hard and held 77 meeting, consuming 385 hours in deliberations. This was followed by the Implementation Commission detailed report that was completed in one year. The distinct part of the whole process was that all the significant political parties were part of this process and thus owned the final report. The central theme of the 18th Amendment was devolution of a number of ministries to the provinces. Thus, it was supposed to be a big step forward to meet the popular demand of provincial autonomy.

Strangely enough as the time passed one could see that there is reluctance on the part of decision makers to implement the 18th Amendment in letter and spirit. One glaring example is Education which was one of those subjects that were devolved to the provinces in the 18th Amendment. There are certain instances that suggest that the government has already started rolling back the Amendment.

One example is the National Commission for Human Development (NCHD). In 18th Amendment, the commission was devolved. Quite contrary to this, no step was taken to implement this decision and as a result the NCHD is still working. Similarly, the National Vocational and Teacher Training Commission was also devolved in the 18th Amendment. The commission is resurrected again, with its headquarter based in Islamabad.

Another example is that of Higher Education Commission (HEC). After the 18th Amendment, certain legislation was requited for restructuring HEC. No step has been taken towards this direction.

These examples are sufficient to realise that the government is not serious in implementing the provision in true letter and spirit. This has been done either by procrastinating the process, defying the provisions or misinterpreting and misconstruing them. The repercussions of this roll back could be serious and far-reaching. The perceived roll back would suggest that the long deliberations of the committee on the 18th Amendemnt and the Implementation Commission were exercises in futility. This would mean negating the tremendous efforts and hard work of all the representatives of national political parties for two years. This would also mean putting the credibility of the government at stake.

A great legal question is whether that we are violating the constitutional provisions by not acting upon them. As mentioned before, the 18th Amendment was an outstanding example of national unity as all the political parties signed the document and it was passed by the National Assembly and the Senate. Now if we recoil from the agreed points which have also become the part of the constitution, the small provinces would be disillusioned.

It is high time to take a major decision regarding 18th Amendment. If we are serious about its implementation, let’s act upon the constitutional provisions in letter and spirit. This would mean a step towards realising a genuine demand of provinces for empowerment and autonomy. The other option is to sacrifice the far-reaching impact of 18th amendment for the sake of short term political benefits. The decision in either way is going to play an important role in determining the future direction of Pakistan.

The writer is Professor & Director of Centre for Humanities and Social Sciences at Lahore School of Economics and author of Rethinking Education in Pakistan. He may be contacted at shahidksiddiqui@yahoo.com